Region: Queenstown, Fiordland, The Catlins, Otago

Travel Dates: November 30 – December 8

The plan was elegance. Standing on the grate of the Nevis Highwire Platform, 134 meters suspended above the rocky bed of the Nevis River, I visualized a perfect forward belly dive. I wanted to control the fall, to feel the air catch me like a bird, a graceful submission to gravity in the remote Otago hinterland.

But gravity has a dark sense of humor. As I pushed off to launch, my boot lost traction on the metal edge. Instead of a dive, I slipped. My toes clung to the platform for a fraction of a second too long, tripping me into a clumsy, inverted spin.

The world flipped instantly. The canyon floor rushed up to meet me, not as a picture, but as a blurring streak of grey schist and river water. The sound was the most violent part—a rushing roar of air that started as a whisper and escalated into a deafening scream. I was fully aware this time, unlike the blur of my first jump in Taupo. I watched the canyon walls spin, felt the blood rush to my head, and heard the air getting louder and louder, a physical pressure against my eardrums. Then, the sudden, elastic snap of the rope caught me just before the bottom. I swung there, upside down in the gorge, blood pounding in my ears, laughing at the complete lack of dignity in the fall.

The Admin of Adventure

Queenstown is the adrenaline capital of the world, sitting on the shores of Lake Wakatipu beneath the jagged peaks of the Remarkables. But it is also a logistical headache. I stayed at the Absoloot Hostel, right in the center of the chaos, which put me close to the action but far from convenience.

The parking situation was a test of sanity. You cannot just leave a car in Queenstown. Every evening, I had to move my Toyota Corolla to a free zone twenty minutes away. Every morning, I had to walk twenty minutes back to retrieve it. It wasn’t freezing, and thank god it wasn’t raining, but the morning air was sharp enough to make me swear I would never bring a car here again. It was the mundane tax you pay for the thrill: for every second of freefall, there is an hour of moving a vehicle.

After the bungee, I took the Shotover Jet. It is the same concept as Taupo—speed and spins—but the setting changes everything. The Shotover River was once known as the richest river in the world during the gold rush of the 1860s, but today the gold is the tourism. Here, you are in a narrow canyon. The walls feel claustrophobic, rushing past your ears inches away. The driver skirts the rock faces with millimeters to spare. It is loud, fast, and violent.

But I still had energy to burn. I took the Skyline Gondola up Bob’s Peak, intending to climb Ben Lomond. The hike starts pleasantly enough in the tussock, but as I climbed higher toward the saddle, the weather turned. The clear sky dissolved into a grey wall of rain and wind. I pushed to the saddle, but the peak was swallowed by cloud. It was pointless to continue. On the way down, wet and defeated by the elements, I met a climber named Eduardo. He was Italian, moving with the easy grace of someone who spends a lot of time on rocks. We struck up a conversation about the weather and climbing routes, and we exchanged numbers—a small connection that would become significant later in the trip.

The Key Swap

On December 2nd, I left the noise of Queenstown for a logistical gamble on the Routeburn Track.

I had arranged a key swap with Monika, a Polish traveler I had met back at the White Elephant hostel in Motueka. She wasn’t alone; she was traveling with Marcelina, another Polish girl, and Marta, an Italian. The plan was simple but required immense trust: I would hike from the Queenstown side (Routeburn Shelter), and they would hike from the Fiordland side (The Divide). We would meet in the middle, swap car keys, and drive each other’s vehicles to the end of the track.

Handing over the keys to a rental car—my home and transport—to people I didn’t know intimately requires a specific kind of traveler’s faith. As I started the hike at 8:30 AM, a small knot of anxiety sat in my chest. What if we miss each other? What if they aren’t there?

The track erased the worry quickly. The Routeburn is an alpine wonderland that acts as a corridor between Mount Aspiring National Park and Fiordland. I hiked up through the beech forest, the trees dripping with moss, passing the Routeburn Flats Hut where the valley opens up into wide, grassy meadows framed by towering peaks. From there, the climb began in earnest toward the Routeburn Falls Hut. This hut is spectacular—it sits right on the edge of the bushline, hovering above the valley floor with the waterfall cascading over the rock face right next to the deck. I stopped there for a moment, impressed by the architecture of the place; it felt less like a hut and more like an eagle’s nest perched on the cliff.

I pushed on, climbing above the treeline into the alpine tussock. The views here are immense. You look down into the Hollyford Valley, a deep green gash in the earth. I reached the high point, the Harris Saddle (1,255m), around midday. The air was crisp, and the view stretched for miles.

I met Monika, Marta, and Marcelina a little further on, just above Lake Mackenzie. We stopped on the trail, four dusty hikers in the middle of the mountains. The handover was quick—a laugh, a key exchange, a high-five. I handed them my Corolla key; they handed me theirs. It felt like a heist, a successful subversion of the expensive shuttle bus system.

I continued down to Lake Mackenzie, a jewel-like alpine lake that reflects the mountains perfectly. From there, the track descends past the Earland Falls (174m high) and through the mossy, goblin-like forest to The Divide. I even had time and energy to take the side trip to Key Summit. The weather was an anomaly—perfectly calm, with clear visibility stretching all the way to the Darran Mountains of Fiordland. I could see the path I had walked and the path ahead, the alpine tarns reflecting the sky like scattered coins.

I finished by 6:00 PM, reaching their car at The Divide. Because they had started from the Divide, their drive back to Queenstown was significantly shorter than mine. I drove their car back to Queenstown, wondering if I would be waiting for hours. But the timing was miraculous. I pulled into the meeting spot, and five minutes later, they arrived with my Corolla. It was precision engineering. We swapped the cars back, and I drove my own trusty Toyota back to the Absoloot Hostel for a final night in the city.

The Base Camp

The next morning, I drove south to Te Anau and checked into Te Anau Central Backpackers. This wasn’t just a place to sleep; it was the nerve center of my Fiordland operations. The hostel was busy, humming with hikers prepping gear, but the standout was the receptionist—a local guy who orchestrated itineraries like a conductor.

I arrived with loose plans, and he transformed them instantly. “Milford Sound cruise? I can book you on one in two hours,” he said. “Kepler Track? I see a bunk free at Iris Burn for tomorrow.” He booked it all. I barely had time to put my bag down before I was back in the car, racing towards Milford Sound to make the boat.

The Mirror

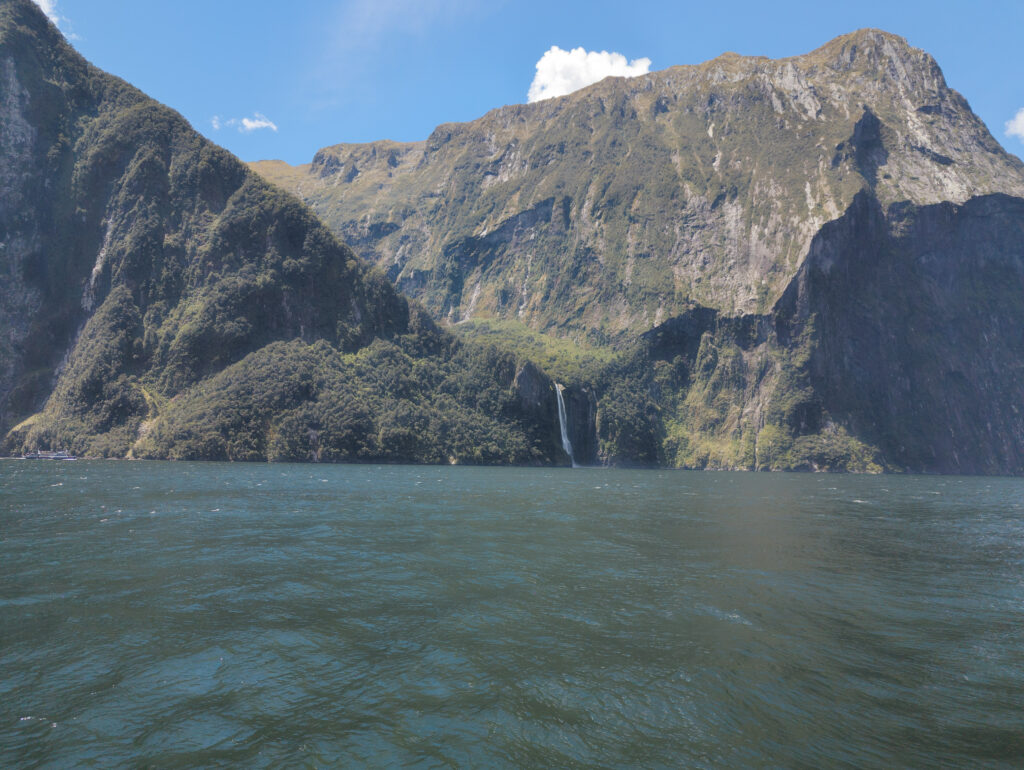

Milford Sound (Piopiotahi) is famous for its moodiness. It rains here 182 days a year, creating thousands of temporary waterfalls that cascade down the sheer cliffs.

I got the other day.

When I arrived, the water was glass. Mitre Peak, usually shrouded in mist, was reflected perfectly on the surface of the fiord. It was disorienting; the sky and the water were indistinguishable. The cruise boat moved through the silence, cutting a line through the reflection. We drifted close to Stirling Falls, where the spray usually soaks the deck, but even the waterfall seemed subdued by the calm. It wasn’t the dramatic, stormy Milford I had seen in photos; it was a rare, serene cathedral of rock and water.

The Friendly Dark

The next day, I left my car at the hostel—safe and free of charge—and started the Kepler Track. I took the water taxi across the lake to start the hike. The Kepler is a purpose-built track, winding through beech forest and up onto a stunning alpine ridgeline.

The hike to the Iris Burn Hut was spectacular. I walked along the knife-edge ridge, looking down into the South Fiord of Lake Te Anau on one side and the Murchison Mountains on the other. The wind can be ferocious here, but I had luck on my side.

I received a message from Eduardo, the climber I met on Ben Lomond. He was heading to Te Anau as well and promised to meet me at the hostel when I finished the track. It was good to know a friendly face would be waiting at the finish line.

The next morning, I woke at 3:50 AM. I wanted to find a Kiwi. The Stewart Island Tokoeka is active at night, and their piercing screech is the soundtrack of the bush. I walked from the hut to the waterfall in the pitch black.

I didn’t hear them. The forest was dead silent. But walking alone in the New Zealand bush at 4:00 AM offers a specific comfort you can’t find elsewhere. There are no snakes here. No bears, no cougars, no wolves. New Zealand separated from Gondwana 80 million years ago, before the evolution of predatory mammals. You are at the bottom of the food chain only because there is no chain. It was just me and the silver ferns catching the beam of my headlamp.

I hiked out as the sun rose, reaching the control gates by 10:00 AM. I hitchhiked back to Te Anau with a Canadian couple and reunited with Eduardo at the hostel.

The Sound of Silence

After the Kepler, I had one final booking: Doubtful Sound.

If Milford is the postcard, Doubtful Sound (Patea) is the novel. It is three times longer and ten times larger. Getting there is a journey into history. We crossed Lake Manapouri and took a bus over the Wilmot Pass. This road wasn’t built for tourists; it was carved out of the rock in the 1960s to support the Manapouri Power Station. We stopped at the visitor center, and I spent thirty minutes absorbing the scale of the engineering. They didn’t dam the river above ground; to preserve the landscape, they drilled a machine hall 200 meters inside the solid granite of the mountain. It is a monument to brute force engineering, yet invisible from the surface.

Out on the water, the scale of the place crushed us. Then, the captain cut the engines. “Listen,” he said.

For a minute, three hundred people held their breath. There was no hum of electricity, no distant traffic, no wind. Just the sound of water dripping off a mossy cliff a hundred meters away. After the scream of the Nevis bungee and the roar of the jet boat, this silence felt heavy, like pressure in the ears. It was the sound of a place that does not care if you are there or not.

The Escape to the Catlins

When I returned to Te Anau, the forecast for Fiordland was grim: heavy rain for days. Eduardo and I looked at the map. The East Coast looked better. We made a snap decision to escape the weather and drove towards the coast, picking up Anais, a French traveler from the hostel who was also looking for an escape route.

The drive was a revelation in rural Kiwi life. As we wound through the green, rolling hills near Gore, something caught my eye above the fields. It was a small agricultural plane, flying incredibly low, banking hard against the treeline. We pulled over to watch. It was a top-dressing plane, spreading lime over the pasture. The skill of the pilot was mesmerizing; he would dive down, release a cloud of white dust that hung in the air like mist, and then pull up sharply at the last second to avoid the hills, only to loop back around and do it again. It felt like watching an airshow, but it was just a Tuesday on a Southland farm. I stood there for twenty minutes, fascinated by the precision of it, wishing I could be up there in the cockpit.

We pushed on to the Catlins, a rugged, windswept corner of the South Island that feels forgotten by time. Our first stop was the Cathedral Caves. These aren’t just holes in the rock; they are massive acoustic chambers carved by the sea, accessible only at low tide. We walked into the darkness, the ceiling soaring thirty meters above our heads. It felt like standing inside the belly of a stone whale, the sound of the ocean echoing against the walls. The sheer scale of it makes you feel small.

We continued to McLean Falls on the Tautuku River. It is a stunning, 22-meter waterfall that cascades over a series of mossy, terraced rocks. The water was roaring, swollen from the recent rains further inland, crashing down into a deep, dark pool below.

Our final stop on the coast was Nugget Point. The lighthouse stands on a precarious, rocky promontory, looking out over a scattering of rocky islets—the “nuggets.” The wind here was ferocious, whipping our hair and clothes, carrying the smell of salt and kelp. We scanned the beaches below for hours, hoping to spot the elusive Yellow-eyed Penguin (Hoiho), one of the rarest penguins in the world. We strained our eyes against the wind, looking for a flash of movement in the scrub, but they remained hidden.

We drove north to Dunedin, checking into a hostel in the city center for the night. The Victorian architecture of the city felt strange after so much wilderness, but the comfort of a warm bed was welcome.

However, the pull of the fiords is strong. Back at the hostel in Dunedin, I checked the Department of Conservation website on a whim. The impossible had happened: a cancellation. A single slot had opened up on the Milford Track, the “finest walk in the world,” starting the very next day. It is almost impossible to book, usually selling out months in advance.

Eduardo looked at me. “You have to do it,” he said.

I didn’t hesitate. I booked the slot. We said goodbye to Anais and the East Coast and drove back to Te Anau, ready to plunge back into the wilderness I had just left. The weather was still predicted to be bad, but for the Milford Track, you go no matter what.

🔒 Protected Content

Enter password to view Part 5 Financial Breakdown.