1. Introduction to Semiconductor Physics

Semiconductors are the foundation of modern electronics. To truly understand how these materials work and why they’re so important, we need to delve into the quantum mechanical principles that govern their behavior. This article will take you on a journey from the fundamental concepts of quantum mechanics to the practical applications in semiconductor devices.

2. Fundamental Concepts of Quantum Mechanics

2.1 The Uncertainty Principle

At the heart of quantum mechanics lies Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. This principle states that we cannot simultaneously know both the position and momentum of a particle with absolute precision. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Delta x \cdot \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI5NyIgaGVpZ2h0PSIzNiIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDk3IDM2Ij48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

Where  is the uncertainty in position,

is the uncertainty in position,  is the uncertainty in momentum, and

is the uncertainty in momentum, and  is the reduced Planck constant.

is the reduced Planck constant.

Similarly, there’s an energy-time uncertainty relation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Delta E \cdot \Delta t \geq \frac{\hbar}{2}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI5OCIgaGVpZ2h0PSIzNiIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDk4IDM2Ij48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

These principles are fundamental to understanding the behavior of particles at the quantum scale.

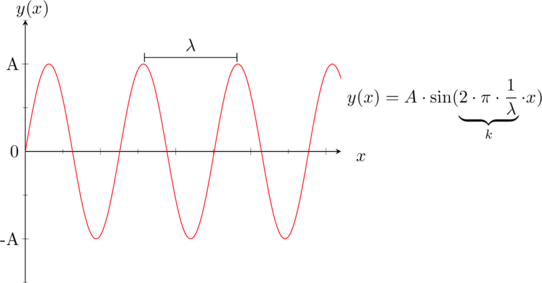

2.2 Wave-Particle Duality

Another key concept is the wave-particle duality, encapsulated in the de Broglie relation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\lambda = \frac{h}{p}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI0NyIgaGVpZ2h0PSI0MCIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDQ3IDQwIj48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

This equation relates the wavelength  of a particle to its momentum

of a particle to its momentum  , with

, with  being Planck’s constant. This duality means that particles can exhibit wave-like properties, and waves can exhibit particle-like properties.

being Planck’s constant. This duality means that particles can exhibit wave-like properties, and waves can exhibit particle-like properties.

2.3 The Wave Function

In quantum mechanics, particles are described by wave functions, usually denoted as  . The probability of finding a particle at a particular position and time is given by the square of the absolute value of the wave function:

. The probability of finding a particle at a particular position and time is given by the square of the absolute value of the wave function:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[P(x,t) = |\psi(x,t)|^2\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxNDMiIGhlaWdodD0iMjIiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxNDMgMjIiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

3. The Schrödinger Equation

The cornerstone of quantum mechanics is the Schrödinger equation. In its time-independent form for a one-dimensional system, it’s written as:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} + V(x)\psi = E\psi\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxOTYiIGhlaWdodD0iMzkiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxOTYgMzkiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

Where  is the mass of the particle,

is the mass of the particle,  is the potential energy, and

is the potential energy, and  is the total energy.

is the total energy.

For many systems, this equation can be simplified to:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} = -k^2\psi\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI5OCIgaGVpZ2h0PSIzOSIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDk4IDM5Ij48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

Where  is the wave number, related to the particle’s energy and mass by:

is the wave number, related to the particle’s energy and mass by:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[k = \sqrt{\frac{2mE}{\hbar^2}}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI5NCIgaGVpZ2h0PSI0MyIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDk0IDQzIj48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

The solutions to this equation are sinusoidal functions, which form the basis for understanding electron behavior in semiconductors.

In quantum mechanics,

does directly relate to the momentum of the particle

. From standard physics we know equation

1

(1)

When inserting equation ?? in equation

1 We get equation

2 and when we rearrange everything equation

3.

(2)

(3)

Furthermore we know from the figure above that

When we insert this in equation

3 we get after some rearinging equation

6 which is the same as equation ??.

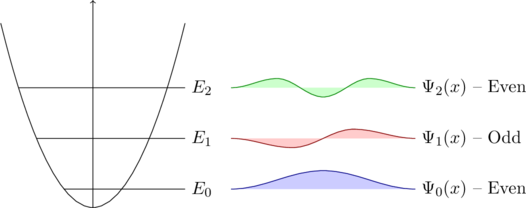

0.0.1. Infinite Potential WellNow we want to find a solution to the differential equation. Let’s assume we have a cube of silicon. The electrons are for sure inside this cube/lattice. So the probability that they are outside of the latice is zero. This behaviour can also be described with the graphic below:C

}For the condition of a solution of the differential equation one can say that the probability of finding an electron must be zero at both ends, therefore the only solution would be a sine (see the possible solutions for the differential equation).

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Psi_0(x)=A_1\sin(k\cdot x)\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxNTkiIGhlaWdodD0iMTkiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxNTkgMTkiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

Furthermore we now that

therefore

. So therefore k can only take certain values, which means the energy is restricted to certain values. The last thing that remains now is to solve for

. We further know equation

4, which says integral of the probability of the particle must be one.

(4)

Therefore we end up with the following:

(5)

(6)

link to sphere (7)

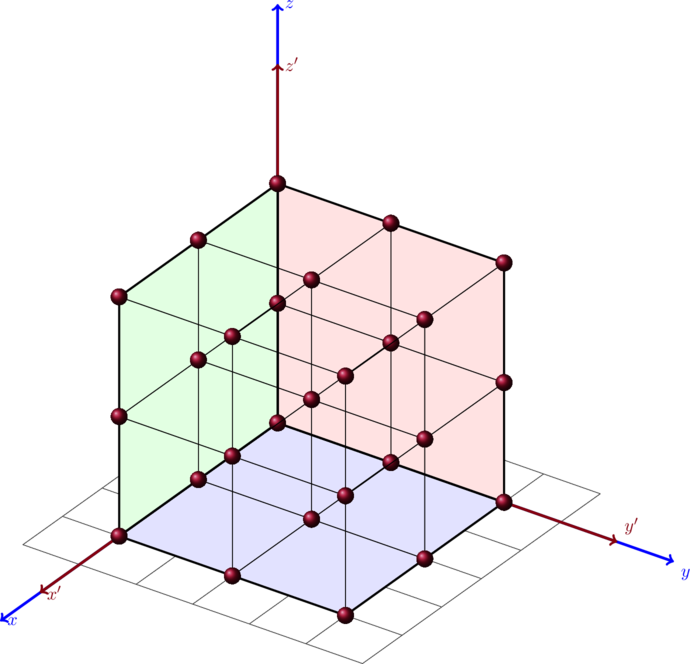

Now want to calculate

. To do that we have to calculate the total number of states divided by the total volume of the semiconductor.

(8)

Assuming that the apples are equally spaced as in the plot above one can say that eacht apple is in a distance to the other with a distance of

. The density apple per volume is in this case

which is one apple per

. The total number of apples is know the volume divided by the apple density

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[N=\frac{V}{\frac{1}{a^3}}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSI2MCIgaGVpZ2h0PSI0NCIgdmlld0JveD0iMCAwIDYwIDQ0Ij48cmVjdCB3aWR0aD0iMTAwJSIgaGVpZ2h0PSIxMDAlIiBzdHlsZT0iZmlsbDojY2ZkNGRiO2ZpbGwtb3BhY2l0eTogMC4xOyIvPjwvc3ZnPg==)

The volume of a spherical shell is

. From before we know that the states of an electron are defined like the following:

therefore the states are in a distance to each other of

. Futher more we can say that we have a state volume, therefore

in this volume is just

which is

and therefore

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[N=\frac{4 \cdot \pi \cdot k^2 \cdot \Delta k}{(\frac{\pi}{L})^3}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxNDMiIGhlaWdodD0iNDUiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxNDMgNDUiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

When we only take the positive k_x, k_y, k_z direction we also get a factor of

.

The density of states in a certain volume is then given by the following formula:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{N}{L^3}=\frac{1}{8}\cdot\frac{4 \cdot k^2 \cdot \Delta k}{(\pi^2}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxNTAiIGhlaWdodD0iNDQiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxNTAgNDQiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

Now we want to substitute

with

. We already know:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{aligned} k &=\sqrt{\frac{2 m E}{\hbar^2}} \\ \frac{dk}{d E} &=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2 E}} \\ d k &=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{E}} d E \end{aligned}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxNDkiIGhlaWdodD0iMTQyIiB2aWV3Qm94PSIwIDAgMTQ5IDE0MiI+PHJlY3Qgd2lkdGg9IjEwMCUiIGhlaWdodD0iMTAwJSIgc3R5bGU9ImZpbGw6I2NmZDRkYjtmaWxsLW9wYWNpdHk6IDAuMTsiLz48L3N2Zz4=)

With this information we can then replace k in the original equation which results in the following:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{aligned} &\frac{4 \cdot \frac{2 m E}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{E}} d E}{8 \pi^2} \\ &g(E) d E=\frac{2 \pi(2 m)^{3 / 2}}{n^3} \sqrt{E} d E \end{aligned}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIyMTkiIGhlaWdodD0iOTgiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAyMTkgOTgiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

And because an electron can have an up and down spin we get the following:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[&g(E) d E=2 \cdot \frac{2 \pi(2 m)^{3 / 2}}{n^3} \sqrt{E} d E\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIyNDEiIGhlaWdodD0iNDEiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAyNDEgNDEiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{-\hbar^2}{2 m} \frac{\partial^2 \Psi}{\partial x^2}=i \hbar \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t}\]](data:image/svg+xml;base64,PHN2ZyB4bWxucz0iaHR0cDovL3d3dy53My5vcmcvMjAwMC9zdmciIHdpZHRoPSIxMzUiIGhlaWdodD0iMzkiIHZpZXdCb3g9IjAgMCAxMzUgMzkiPjxyZWN0IHdpZHRoPSIxMDAlIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjEwMCUiIHN0eWxlPSJmaWxsOiNjZmQ0ZGI7ZmlsbC1vcGFjaXR5OiAwLjE7Ii8+PC9zdmc+)

or

1. intrinsic & extrinsic semiconductors

Where p-type and n-type materials meet is called a p-n junction. Electrons from the n-type material move to the p-type material and close the holes and vice versa. This is called \textbf{diffusion} and leads to a {depletion layer}

In an n-channel mosfet the inversion is called inversion because the p-type material looks like n-type.

![]()

![]() is the uncertainty in position,

is the uncertainty in position, ![]() is the uncertainty in momentum, and

is the uncertainty in momentum, and ![]() is the reduced Planck constant.

is the reduced Planck constant.![]()

![]()

![]() of a particle to its momentum

of a particle to its momentum ![]() , with

, with ![]() being Planck’s constant. This duality means that particles can exhibit wave-like properties, and waves can exhibit particle-like properties.

being Planck’s constant. This duality means that particles can exhibit wave-like properties, and waves can exhibit particle-like properties.![]() . The probability of finding a particle at a particular position and time is given by the square of the absolute value of the wave function:

. The probability of finding a particle at a particular position and time is given by the square of the absolute value of the wave function:![]()

![]()

![]() is the mass of the particle,

is the mass of the particle, ![]() is the potential energy, and

is the potential energy, and ![]() is the total energy.

is the total energy.![]()

![]() is the wave number, related to the particle’s energy and mass by:

is the wave number, related to the particle’s energy and mass by:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{aligned} k &=\sqrt{\frac{2 m E}{\hbar^2}} \\ \frac{dk}{d E} &=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2 E}} \\ d k &=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{E}} d E \end{aligned}\]](https://mmeyer.tech/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b8664d1784f96fbb3c4fb51b348340af_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{aligned} &\frac{4 \cdot \frac{2 m E}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{2 m}{\hbar^2} \frac{1}{E}} d E}{8 \pi^2} \\ &g(E) d E=\frac{2 \pi(2 m)^{3 / 2}}{n^3} \sqrt{E} d E \end{aligned}\]](https://mmeyer.tech/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0475ceb681382ad3b1a069b1868240e0_l3.png)

![]()

![]()